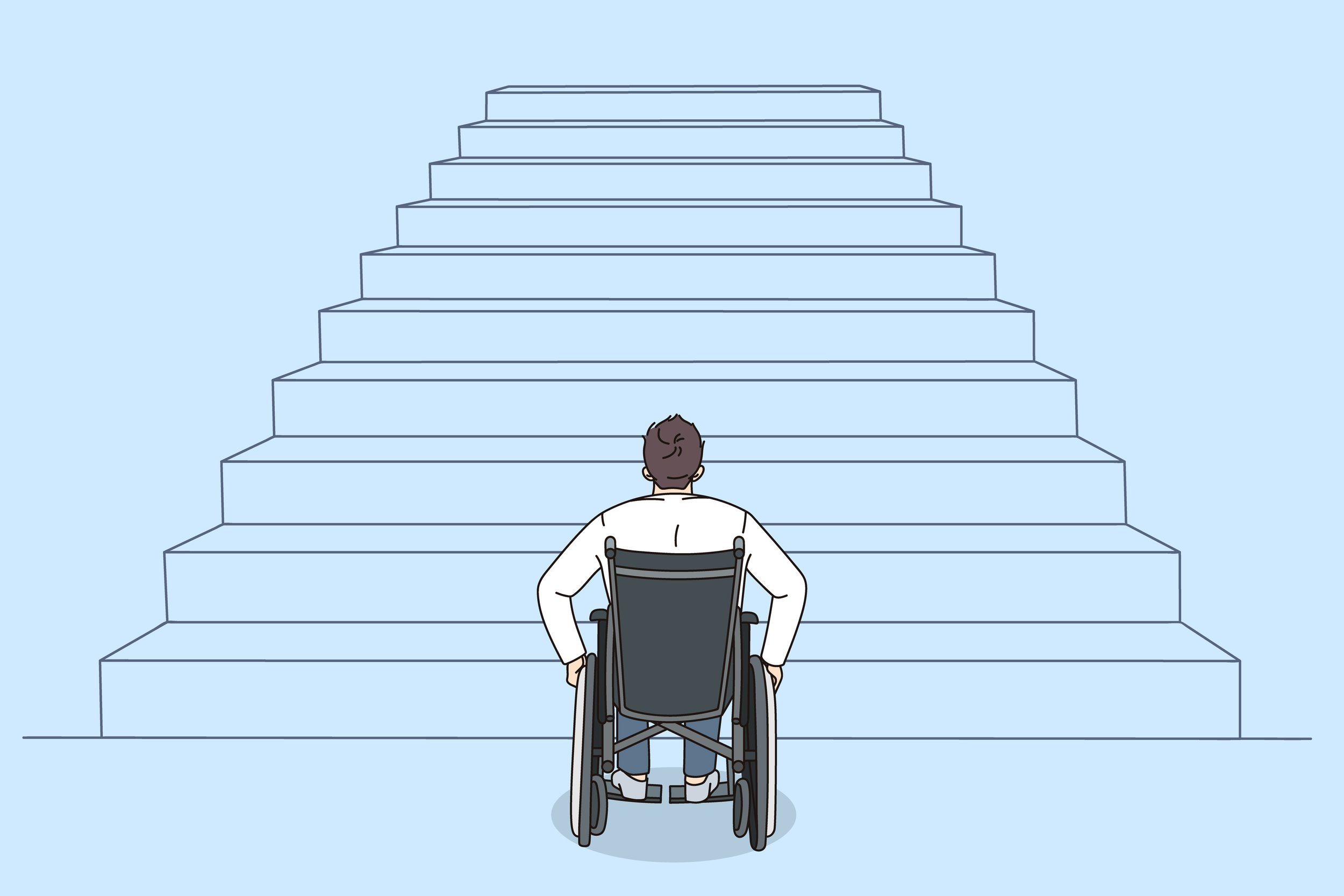

How Medical Schools Discriminate Against People With Disabilities

Technical standards are tools of discrimination.

An interview with Emily Gordon

Image by Erumaira

Emily Gordon, the author of “Wheels of Injustice: How Medical Schools Retained the Power to Discriminate Against Applicants in Wheelchairs in the Era of Disability Rights,” spoke with our editor-in-chief Jason Silverstein about why medical schools developed “technical standards” for applicants, how they are used to discriminate against people with disabilities, and why it is so hard to know how much damage has been done. Here’s what she had to say.

The story of discrimination against people with disabilities by medical schools is a challenging one. It is written into the rules of when you apply to medical school and you check the box that you meet all of these technical standards for every single medical school. It is hard to fully understand who didn’t even apply in the first place because they were discouraged by the lack of representation or the standards themselves.

Ultimately, there is a certain population we cannot capture who likely applied to med schools and didn't get in for reasons we can never really know, and people who were in wheelchairs and had never seen anyone go to medical school and it wasn’t presented as an option for them.

In Southeastern Community College v. Davis, a student who applied to nursing school and basically went through the application process was told that she couldn't go to nursing school because of her disability. This decision worked its way all the way to the Supreme Court. A lot of other actors got involved in that discussion, including, but not limited to, the AAMC [Association of American Medical Colleges].

No one was saying that medical schools were suddenly going to be forced to change their standards about how they were admitting people. But it seems like the AAMC perceived it that way. That then caused them to create these “technical standards” in support of why medical schools should have flexibility to decide who to admit.

The technical standards stated people have to be able to meet certain physical competencies, like being able to perform CPR or certain tasks that would be incredibly challenging for people with certain disabilities and specifically people who use wheelchairs.

Basically as the case is working its way up to the Supreme Court, the AAMC hears about it and releases their technical standards report in January 1979. Then, they sent in an amicus brief in February. Only in June did the Supreme Court announce their decision in Davis [Which ruled that schools may consider disability in admissions, but cannot exclude an ““otherwise qualified” applicant solely on the basis of a disability.]

These standards were created in the late 1970s, but they still exist. These technical standards are basically universal and ultimately it is up to schools if they enforce these standards. If someone applies to medical school and isn’t capable of doing one of the tasks, then medical schools can choose to accept them or reject them. The technical standards are tools of discrimination that exist that can be wielded at the whim of institutions to exclude applicants.

There are people who have gotten in. But they often needed advocates on their side and had to portray themselves in a certain way. They had to focus on how they were not going to be a burden to the school, focus on their resilience, and focus on all of their incredible accomplishments and try to deemphasize the accommodations they would be requiring. And a lot of people describe having gone to medical school in a wheelchair and having experienced bias and discrimination and a lot of assumptions about their capabilities.

James Post became quadriplegic in a diving accident and has been using a wheelchair since. He was interested in medicine and decided to apply to medical school. In the early 1990s, he applied to 10 medical schools and several offered interview invitations.

When he would go to the medical schools to interview, Post would explain that he might need some assistance to achieve the technical standards. He said he planned to hire assistants and he was interested in specialities that didn’t necessarily require precise motor skills.

As he was interviewing, there was a lot of pushback. One interviewer said to him, “I want you to go to the school of performing arts and tell them you want to be a concert pianist and see what they have to say. That’s how I feel about you becoming a physician.”

Ultimately, Post was rejected from every medical school he applied to. Some even said it was because of his disability. But he was still really interested in going into medicine, so he shared his story with the local press which then got picked up by the national press and he went on a television show and found an advocate for him. Post applied to Einstein and ultimately was accepted and graduated and is now a practicing physician.

While the Americans with Disabilities Act did a lot of amazing things, there was a lot of ambiguity about who counted as having a disability and how it was going to be enforced. In the context of how it is used for medical schools, applicants still had to be able to perform “essential functions of programs.” They can receive reasonable accommodations to do so, but they cannot result in any fundamental alteration to the program. Schools are allowed to make an individual judgment about what are the essential functions of programs and what counts as reasonable accommodation.

What are medical schools really so afraid of? It reflects the discomfort in the medical community about losing the authority to gatekeep who can enter the profession. It is a practice that goes back centuries of being able to say what should a physician look like—to say that a physician should be white, male, able-bodied, Christian. And that has been used to exclude anyone who doesn’t fit that image.